Posts Tagged field guide

Guide to Distinguishing Western Pond Turtles (Actinemys spp. ) from Common Pond Sliders (Trachemys spp.)

Posted by Matthew Bettelheim in Field Guide, Herpetology, Western Pond Turtle on March 11, 2024

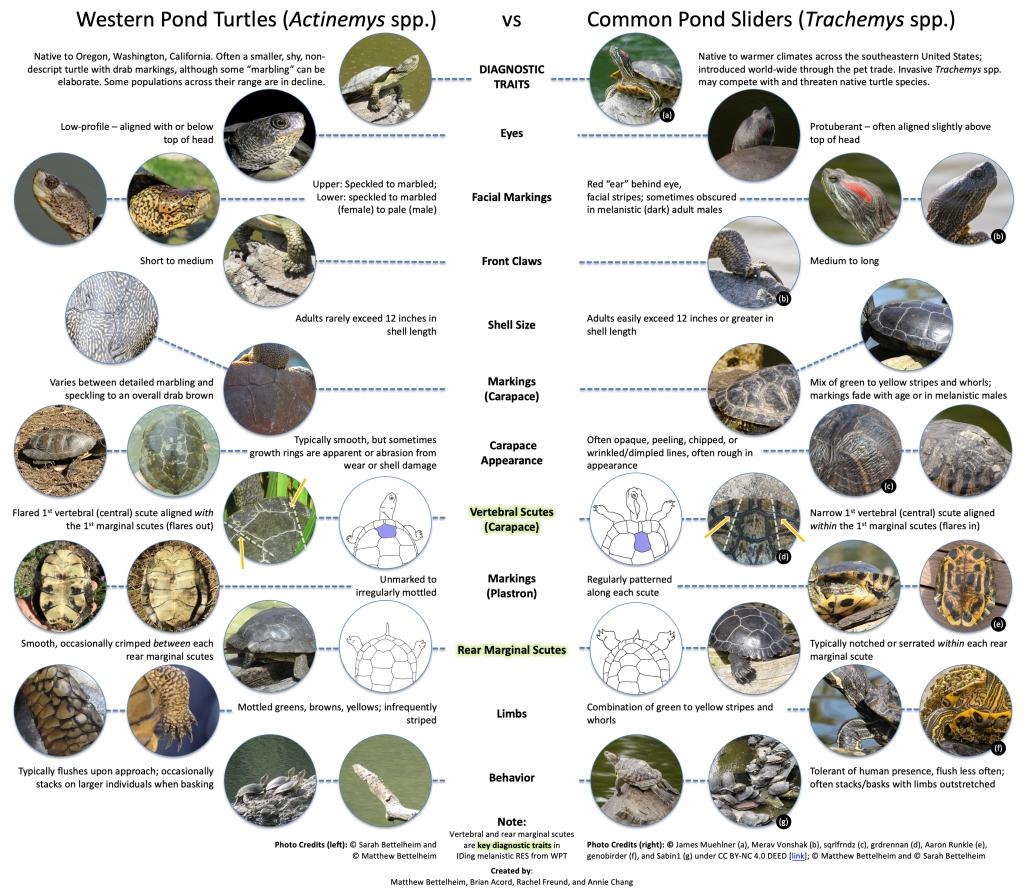

Laypersons and professional scientists alike are regularly confounded when trying to distinguish between northwestern/southwestern pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata / A. pallida) and any of a number of common pond sliders (Trachemys spp.) like the red-eared slider (T. scripta elegans).

You are not alone!

As pond sliders age, their distinct markings can diminish; male sliders in particular often become melanistic (an increase in dark pigmentation) with age that masks any distinctive markings (like the “red-ear” and striping) and/or enhances secondary markings (speckling) that more closely resemble a western pond turtle. While the marbling and speckling of certain western pond turtles is unmistakable, these characteristic markings can become muted as well through age and wear/tear; some western pond turtles are drab brown and any marbling only becomes apparent when submerged in the water, if at all.

Why is this important? With certain populations of the west’s native western pond turtle experiencing threats from climate change, habitat loss, disease, etc., it is important for Agency personnel and land managers to have the most accurate representation of where western pond turtles are, and are not; just as important is to know where invasive turtles like Trachemys spp. are encroaching on western pond turtle habitat. The western pond turtle is a California Species of Special Concern, and is now a candidate for listing under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Establishing the species’ range is critical to future management decisions.

To help iNat users and the public distinguish between these two species, I’ve partnered with @cnddb_brian, Rachel Freund, and Annie Chang to create an illustrated guide to help us sort out those tricky turtles. Remember, not one diagnostic trait alone is necessarily the silver bullet; we’ve identified 11 key traits that, between them, should help if you can get a clear look at a turtle from any one angle. Some traits might contradict others; turtles are variable, not only between species but also within species. You might not be able to state whether the turtle you are looking at has short-to-medium or medium-to-long claws, or whether it is more-than, or less-than 12 inches long from 200 feet away – that’s understandable. Hopefully, there are enough clues among these 11 to help you make an educated decision.

That being said, the two key diagnostic traits we would hang our hats on are (#7) the arrangement of the 1st vertebral and 1st marginal scutes (see Footnote #1) on the carapace immediately behind the turtle’s head/neck, and (#9) whether the rear marginal (outermost) scutes are serrated/toothed within each scute (= slider), or only show interruptions (if at all) at the seam between each scute (= western pond turtle). If you can get a good look, or a sharp photo, that shows either or both of these traits, you’ll make your job and ours a lot easier :).

The other 9 traits are also important, but there is so much variability that some of these can be open to interpretation depending on time-of-day/lighting, distance, wear and tear on the shell, the turtle’s angle of repose, and/or the quality of the photograph. Personal biases should be considered too:

- Don’t assume it is a slider because you are in an urban setting;

- Don’t assume it is a native turtle because you are in a natural wilderness area;

- Don’t assume it’s either species because the other has never been reported there before.

Those can be context clues, but not the sole basis of an identification. That being said, consider the natural range of the species and use common sense. Many pond sliders reported in southeastern states get improbably flagged by the image recognition software as western pond turtles despite a user’s location data. If you are in Texas or Maine, you can probably (usually?) make a safe assumption the turtle in front of you is not a western pond turtle. Unless you have solid evidence to the contrary – stranger things have happened, and unfortunately, people move turtles around.

Many of the photos uploaded to iNaturalist are nowhere near as sharp or detailed as the representative photos we’ve curated here. We’ve selected sharp, diagnostic photos to help train you and your eye to make heads or tails of those heads and tails. These photos are meant to condition you for when conditions in the field are less than optimal. And trust us – in the field, the turtle is going to going to haul itself onto a log with a carapace coated in algae, or the marginal scutes will be gnawed to tatters by a predator, or there will be a tule or blade of grass across the photo blocking that one key diagnostic trait we suggested you look for.

And remember, this guide is only meant to help users distinguish between native western pond turtles and non-native pond sliders, rather than identify either to a specific species. The north and southwestern pond turtles are more or less indistinguishable except by their geographic location and, if the turtle is in hand (please don’t capture/handle them), the sometimes-presence or absence of an “inguinal scute” hidden along the groin area of the shell. Meanwhile, there are any number of pond sliders to choose from. This guide, in essence, is a binary guide: native turtle, or nonnative turtle. If that is all you are able to determine, or if this guide helps you look for that one key diagnostic trait so that you can make that decision, we’ve done our job.

Good luck!

You can also download a pdf of the guide using this link.

Footnote #1: scute = the individual plates on the carapace [top shell] and plastron [bottom shell]

Photo Credits (left): © Sarah Bettelheim and © Matthew Bettelheim

Photo Credits (right): © James Muehlner (a), Merav Vonshak (b), sqrlfrndz (c), grdrennan (d), Aaron Runkle (e), genobirder (f), and Sabin1 (g) under CC BY-NC 4.0 DEED; © Matthew Bettelheim and © Sarah Bettelheim

Created by:

Matthew Bettelheim, Brian Acord, Rachel Freund, and Annie Chang

Book Review: Trees of Western North America

Posted by Matthew Bettelheim in Book Reviews, Botany, Field Guide, Natural History on November 19, 2014

Trees of Western North America, by Richard Spellenberg, Christopher J. Earle, and Gil Nelson, Princeton University Press (http://press.princeton.edu), 2014, 560 pages, $29.95

Trees of Western North America, by Richard Spellenberg, Christopher J. Earle, and Gil Nelson, Princeton University Press (http://press.princeton.edu), 2014, 560 pages, $29.95

In this latest installment in the Princeton Field Guides series, botanists and ecologists Richard Spellenberg, Christopher J. Earle, and Gil Nelson have introduced two new guides to the trees of North America, Trees of Western North America (reviewed here) and its companion guide, Trees of Eastern North America.

With Trees of Western North America, users will have at their fingertips a guide to the identification of 630 tree species accompanied by detailed color paintings, regional interstate range maps, and a Quick ID that summarizes key tree characteristics. For every species, the illustrations depict tree form, branches and twigs, leaves, fruits, flowers, and bark. Given the number of trees tackled here, the text is understandably brief but thorough, drilling down to the bare essentials. Still, most accounts close with notes describing any particulars that make each species unique: conservation status, varieties, hybrids, history. Whether you’re faced with a saguaro or a sequoia, a hawthorn or a hemlock, this easy guide will surely get you to the birch in time.

Book Review: Rare Birds of North America

Posted by Matthew Bettelheim in Book Reviews, Field Guide, Natural History, Ornithology on June 3, 2014

Rare Birds of North America, by Steve N. G. Howell, Ian Lewington, and Will Russell, Princeton University Press (http://press.princeton.edu), 2014, 448 pages, $35.00

Rare Birds of North America, by Steve N. G. Howell, Ian Lewington, and Will Russell, Princeton University Press (http://press.princeton.edu), 2014, 448 pages, $35.00

Though I’m a rank and file wildlife biologist, I consider myself more a birdwatcher than a birder. So it was with some surprise when I cracked open Rare Birds of North America to find that this new guide to rare North American birds dealt not in threatened or endangered species, but in vagrant species – those that turn up in scarce numbers (averaging 5 or fewer) at locations atypical of their natural range during migration events. Knowing this is key to appreciating the scope of this guide, which looks at some 262 straggler species who – whether by misorientation or weather or bad directions – run the risk of waking up one morning to find a gaggle of bino-eyed birders ogling them to check another vagrant off their life list.

Vagrancy is a curious thing in birds, a phenomenon poorly understood even today. But as authors Howell, Lewington, and Russell so carefully explain in the introduction, there are no shortage of explanations for how migratory birds stray off course. Birds are their own pilots with an array of navigational tools at their disposal, be it reading the landscape by sight, following celestial features (stars, sun, moon), or following the Earth’s magnetic field. But like pilots, their tools can be hampered by inclement weather or poor data, causing birds to turn back from exhaustion or give in to prevailing headwinds. Similarly, whether their migratory patterns are learned or innate, a miscalculation of time, distance, or environmental cues (barometric pressure, wind direction) can lead birds to over- or undershoot their destinations. Every species is different, but certain vagrants in North America are more common than others (East Asian species typically occur in western North America, Western Eurasian species typically occur in eastern North America), and shrewd birders keen on bird migration and weather systems can predict vagrants with surprising accuracy (see, for example, Derek Lovitch’s How to be a Better Birder).

Once the basis and reasoning for vagrant birds occurring in North America is established, Rare Birds… spills into a field guide to said rarities. Not a guide you’d necessarily lug around in your pants pocket – odds are if you’re chasing vagrants through the woods, you’ve got your eyes glued to your binoculars, not your bird guide – but surely one you’d consult as you planned your trip, on the plane as you share airspace with fellow migrants, or in the passenger seat as you hurtle towards your destination. The species accounts are quick and clean, with an emphasis on a description of their distribution and status (essentially, where they should be, and where vagrants have turned up) backed by a discussion of vagrancy patterns and field identification. Ian Lewington’s illustrations are exceptional, inside and out. The cover illustration of a Siberian accentor looks like a gritty, bokeh-styled field photograph I would be proud to have taken. So if you take your birds rare, don’t miss out on this impressive testament to the study of vagrancy in North American birds.

Book Review: Bumble Bees of North America

Posted by Matthew Bettelheim in Book Reviews, Entomology, Field Guide, Natural History on May 12, 2014

Bumble Bees of North America: An Identification Guide , by Paul H. Williams, Robbin W. Thorp, Leif L. Richardson, and Sheila R. Colla, Princeton University Press (http://press.princeton.edu), 2014, 208 pages, $24.95

Bumble Bees of North America: An Identification Guide , by Paul H. Williams, Robbin W. Thorp, Leif L. Richardson, and Sheila R. Colla, Princeton University Press (http://press.princeton.edu), 2014, 208 pages, $24.95

With spring upon us, the timely arrival of Bumble Bees of North America on bookstore shelves is as welcome as its namesake insects are in gardens. The bumble bee’s dutiful attention to attending (and pollinating) flowers as they forage for pollen makes them an invaluable natural ally and a critical asset to our planet’s fragile ecosystems. But for a species we depend on so intimately for our food supply, there is surprising difficultly in clearly distinguishing between species – even among bee systematists – without the illumination of molecular analysis. Without such modern amenities in the field, entomologists are left to untangle species from hair color patterns, a maneuver further complicated by caste (queen or worker), or morphological characteristics of the face and genitalia which, for the layperson, is often too close for comfort.

Given that the last comprehensive guide to North American bumble bees was published in 1913, Williams, Thorps, Richardson, and Colla’s Bumble Bees of North America offers a much-needed review of the status and identification of the 46 bumble bee species north of Mexico. Notwithstanding several cursory chapters on natural history, bumble bee forage by ecoregion, or decline and conservation, Bumble Bees of North America is otherwise a species identification guide based on four principal groups derived from either a quick, simple key (p 50), or an advanced main key (p 168-198) that requires a microscope or hand lens. Especially helpful are the color plates that illustrate a majority of the keys’ couplets. Accompanying each species entry are the expected distribution maps, representative photos, and identification characters, as well as diagnostic color-pattern diagrams meant to illustrate the hair color patterns.

Where the guide appears to fall short is its failure to provide direction on how to actually read the color-pattern diagrams, which should be the guide’s hallmark feature. Take the characters of the Vosnesensky bumble bee, described to have “Hair of metasomal T3 black (contrast B. vandykei), T4 almost entirely yellow with just a few black hairs near the midline (contrast B. caliginosus, B. vandykei), S2-5 with black fringes at the back (contrast B. caliginosus) or very rarely with yellow at the sides” and “Male… hair color pattern… metasomal T5 at the sides with yellow”. It was only after I carefully reexamined the guide cover-to-cover to make sure I hadn’t overlooked an introductory paragraph or legend that I found a diagrammatic figure in the glossary that included among the labels “Tergum (T)” and “Sternum (S)”, which led me to glossary definitions for each term. A simple diagrammatic figure laying out each T# and S# plate designation on a sample color-pattern diagram preceding either of the keys would have gone a long way toward easing a layperson effortlessly into the keys.

That being said, Bumble Bees of North America marks a much-needed milestone in the ability of scientists and citizens alike to sort bee species found afield and at home. With bees on the decline, the ability to identify and inventory the buzz in our backyards may prove critical in future conservation efforts.

In Memorium: Robert C. Stebbins *UPDATE*

Posted by Matthew Bettelheim in Herpetology, History, News and Research, Stebbins on October 8, 2013

Robert Cyril Stebbins, Kensington Studio, 2004 w/ the Permission of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, UC Berkeley

On September 23, esteemed herpetologist Dr. Robert (“Bob”) Cyril Stebbins (March 31, 1915 – September 23, 2013) passed away in his sleep at the age of 98. In the days since his passing, articles and obituaries have sprung up across the county commemorating Dr. Stebbins not only for his great accomplishments, but also his kindness.

Three new obituaries from the New York Times, LA Times, and SF Gate are listed below for those interested in learning more about one of California’s finest environmental heroes.

New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/08/us/robert-c-stebbins-chronicler-of-western-reptiles-and-amphibians-dies-at-98.html?_r=0

LA Time

http://www.latimes.com/obituaries/la-me-robert-stebbins-20131006,0,6487001.story

SF Gate

http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Robert-C-Stebbins-UC-Berkeley-biologist-dies-4867758.php

For those of you who wish to share your thoughts, memories, and reflections of time spend with Dr. Stebbins as a friend, student, or colleague, or as a naturalist in the great outdoors with his field guides in hand, I encourage you to visit this earlier post, In Memorium: Robert C. Stebbins (March 31, 1915 – September 23, 2013), and record a note in the “Comments” to share your love and respect for the late Dr. Stebbins with the herpetological community.

![]()

In the Spring of 2012, the Stebbins family granted me permission to reprint extracts from his memoir, a work-in-progress he offered freely to the herpetological community. For more information on this serial column featuring the life and times of Dr. Robert C. Stebbins, please visit this post.

![]()